America’s Sweethearts: Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders and the Brand of Unattainability

Thoughts from an eating disorders therapist.

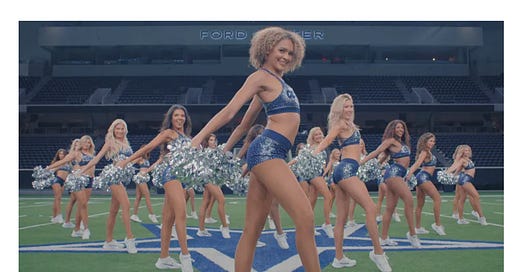

I spent the last two days binge-watching the second season of America’s Sweethearts: Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders on Netflix. (the lightest of spoilers ahead). For those who haven’t gotten into it, it follows the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders (DCC for short) through a season of their cutthroat auditions, game days, and special performances. Typically, it casts special focus on the bright-eyed rookies and the 5th-year veterans as they navigate their way in and out of DCC life, respectively.

As I slowly came out of my reality show haze, I found myself reflecting on body image within the DCC and the dance world more generally. I don’t have the lived experience of being a dancer but as an eating disorders psychologist, many of my clients have. As you can probably guess, dance and cheerleading are two sports rife with eating disorders. Essentially, any sport that has a strong need for bodies to look a very specific way will carry that risk, and the more rigid the requirements the generally higher risk of eating disorders. For example, ballet has an exceptionally high rate of eating disorders, in part because of the rigid ideal that a ballerina is supposed to live up to body-wise.

I found myself feeling a little confused when watching this new season about how many of them spoke about body image. It would almost feel like they were moving towards a more progressive view of body image, only for the outcome to land pretty flat. In one scene, Kelli (director of the DCC) comments on a rookie’s weight. She asks if her current weight is one she can comfortably maintain (the implication being that she does not want her to go to extremes to stay her current size).

In another interview, she talks about wanting the girls to be healthy and nourished. This is technically positive, as past seasons have gotten criticized for how the directors have picked apart the girls’ bodies. However, the hidden undercurrent remains. If that rookie’s healthy and nourished body looked anything other than thin, she would not be a rookie on the DCC. Healthy and nourished is fine, as long as it still has “the DCC look.” And there is no question, the DCC look is thin.

In this way, I believe that the real brand of the DCC is unattainability. In every single practice and every single day of training camp, they are to show up in full glam, complete with full hair and makeup. This is often after working a full day at the jobs they must maintain to be able to support themselves (NFL cheerleader pay is notoriously low). In both seasons, the complete overwork of the women (including a consistent lack of sleep) is very much glorified. The message is that these women can do it all, do it all beautifully, and do it all perfectly.

The problem is, not even the DCC girls can live up to these sky-high expectations. The cracks start to show from even the first few episodes. One storyline that follows a team captain shows her slowly melting down in real time, as the pressure to be perfect finally gets to her in a way she can no longer ignore. All I could think as I watched that storyline was just how avoidable it all was. If she could just let off a little steam, have been allowed to be human, the meltdown would not have had to happen in the first place.

To be clear, I am not knocking any of the women on the DCC or their bodies. They are amazing athletes, artists and entertainers. As an eating disorder psychologist, I just worry about the messages this culture has that spill over the larger culture. Messages like it is it not ok to be human, you must be perfect. You can be anything you want, as long as you are spray-tanned and dolled up, with thick flowing hair and a thin body. You have to have perfectly white teeth, an athletic build but with shoulders that are not too big, have three jobs but don't offload the stress on anyone else, don't complain about your three hours of sleep, and above all, keep sweet and compliant. Don’t dare demand more, you should be grateful to be here. In the words of The Devil Wears Prada boss Miranda Priestly, a million girls would kill for this job.

In the end, my thoughts are this. The brand of unattainability may sell well, but it isn’t good for any of us in the end. I really do believe artists and entertainers can make beautiful art without selling us this lie of perfection in the process. We deserve to see women celebrated not for how well they disappear into an ideal, but for how boldly they take up space just as they are.